TRES is an art collective whose curiosity focuses on waste: how it exists, why it exists, what it means for humans and nature. “We would like to inspire people to shift their gaze, to look at the things we have rendered invisible as a society,” they explain. Founded in 2009 by three artists—Ilana Boltvinik, Mariana Mañón, and Rodrigo Viñas—they travel the world to observe, collect, and reflect back to us the material they find.

How long have you been working together? How would you describe your work and your artistic backgrounds?

TRES was formed in early 2009, in the context of a workshop-public intervention in the university Claustro de Sor Juana. We are an interdisciplinary collective. Although all of our backgrounds are in art, with each project we expand and contract our collective. We invite people from varied disciplines, such as biology, archaeology, anthropology, sociology and geography to participate in our projects.

We have established a work methodology that involves walks and explorations (inspired by Situationist dérives ) in public spaces as well as scavenging that helps us detect and contextualize waste through meticulous observation. The intimacy with which we, as a collective, live with trash is extended into an aesthetic experience through photography, video, drawing, and public actions.

On one hand, the waste narratives emerge and are made visible with our fieldwork: photography, video and drawing. On the other hand, this initial work is complemented and woven in with statistics, interviews, and art-based research. Visiting paradigmatic waste places in each location is of paramount importance. Dumps, landfills, and transfer stations reinforce a general and ample dimension of waste in each society. This interdisciplinary process helps us render the global dimension of the problem in a way that it is accessible to others.

What sparked your mission to raise awareness through your art? Is there a particular moment or realization that inspired you to focus on the relationship between the natural and built environments?

We love to walk through the streets as a way of knowing a place. These constant walks in Mexico City brought to our attention the many abandoned objects that lay on the streets, not only because no one picked them up, but because they weren’t worthy even of a quick look by any of the pedestrians. We started collecting, classifying, and playing with these objects in order to get a closer look at daily practices of consumption and disposal.

These objects shine back at us all the time, as Jane Bennett wrote: they command our attention. More than an ecological awareness, what interests us is a material awareness: how we use, discard and disregard the material life of objects, before and after we use them. In this sense, garbage for us is more of an ethical or political question that focuses on all the things we leave aside, forgotten. We are interested in our broken relation with the objects that surround us. As John Scanlan states in his book On Garbage , “If we look for connections amongst the variety of hidden, forgotten, thrown away, and residual phenomena that attend life at all times (as the background against which we make the world) we might see this habit of separating the valuable from the worthless within a whole tradition of Western ways of thinking about the world, and that rather than providing simply the evidence for some kind of contemporary environmental problem, ‘garbage’ (in the metaphorical sense of the detached remainder of the things we value) is everywhere” (Scanlan, 2005: 8). Garbage is then a way to address the issues we do not want to speak about in our contemporary societies.

More than thinking of the dichotomy of natural vs. built, we address garbage as a hybrid materiality that has undergone many transformations that demonstrate that the difference between natural and built is breaking down—or more precisely, is a cultural construction.

What’s your process like? How do you find inspiration, how long does a piece take, and when do you determine it’s complete? Where is your work displayed, or how is it distributed?

Usually one thing leads to another; we explore one issue that, more than solving our initial question, opens many more. For example, when collecting rubbish for our first project “un archipiélago de olvidos” (2009) we realized that the cigarette butts escaped everything and everybody. They would hide in the cracks, and people threw them to the street with no remorse. So we drew our attention to this phenomenon. Later, the mobility of these cigarette butts got us thinking of more permanent trash: chewing gum stuck to the sidewalks.

Our projects are usually long term, between six months and a year. They require lots of research and exploration. Also, they are never totally complete. We put a stop at a certain point, usually this is when the information and material we have is too much, and we need to make sense of it.

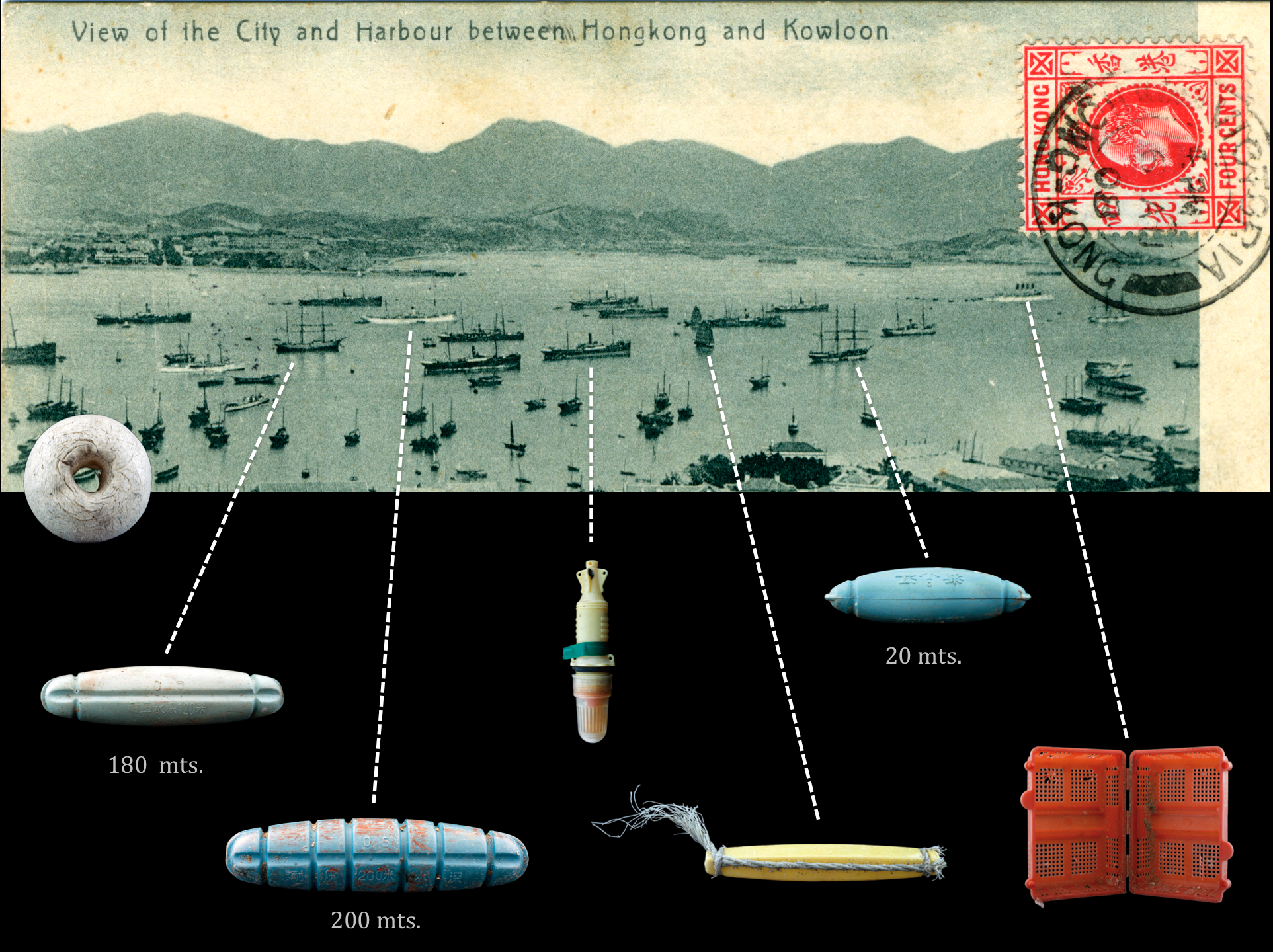

Our work has been displayed in many museums and public spaces in Mexico, Denmark, the U.K., and Hong Kong. [Their work can also be found in book form. ]

Is there anything specific about ocean/water subjects that speak to you as artists?

Marine debris has become our latest obsession. We consider it the proof that garbage is ubiquitous. Trash no longer has a clear frontier. Soda bottles made in China may wash up on a beach in Mexico or Australia; medical waste from New York may be found on the beaches of Brazil or Iceland. Trash from anywhere can be found everywhere. Additionally, all objects are produced with parts from all over the world. With marine debris we address the garbage issue as a global one, a nowhere land that is affecting us all.

Also, marine debris is the proof that materiality is always hybrid. For example, in Australia we found many pieces of plastic on the beaches that have become the temporary home of bryozoans.

What reaction would you like people to have to your work – and what message do you want them to take away?

We do not mean to solve people’s doubts about what should be done with garbage—we hope to open questions. An important issue for us is the intimate relationship we establish with the material culture that surrounds us. We would like to inspire people to shift their gaze, to look at the things we have rendered invisible as a society.

Website: tresartcollective.com