Zaria Forman is an American artist who uses her work to convey the urgency of climate change. Her art has taken her to some of the most remote areas. Zaria’s drawings explore moments of transition, turbulence, and tranquility in the landscape, allowing viewers to emotionally connect with a place they may never have the chance to visit.

1. What sparked your mission to raise awareness through your art? Is there a particular moment or realization that inspired you to draw about subjects affected by climate change?

During my first trip to Greenland, I became aware of how serious the climate crisis is. The local Inuits spoke of vast ice fjords that are not freezing as they once did, challenging the lifestyle of the existing hunting communities that dot the coastlines. The fjords are the communities’ hunting grounds for seal, walrus, and other animals that provide sustenance, warmth and other crucial facets of life necessary for Arctic survival. Insufficient ice severely limits their hunting grounds. Greenland has no railways, no inland waterways, and virtually no roads between towns. Their major method of transportation is by boat around the coast in summer and by dog sled in winter (which, ten years ago, made up most of the year). Without frozen fjords, their dogs and sleds are rendered useless, and many cannot afford to travel very far by boat. This is just one of innumerable ways the warming Arctic is affecting the Inuit way of life. Learning about all of this instilled in me a need to play a part in solving the crisis, with the skills and passion I have for drawing. Beyond Greenland, the entire planet is affected. I followed the meltwater from the Arctic to the Equator in an attempt to draw the connection between two seemingly disparate landscapes that are undoubtedly linked by the climate crisis.

2. How does your process begin and how long does it take you to complete an art piece?

When I travel, I take thousands of photographs. I often make a few small sketches on-site to get a feel for the landscape. Once I return to the studio, I draw from my memory of the experience, as well as from the photographs, to create large-scale compositions. Occasionally I will re-invent the water or sky, alter the shape of the ice, or mix and match a few different images to create the composition I envision. I begin with a very simple pencil sketch so I have a few major lines to follow, and then I add layers of pigment onto the paper, smudging everything with my palms and fingers and breaking the pastel into sharp shards to render finer details.

The process of drawing with pastels is simple and straightforward: cut the paper, make the marks. The material demands a minimalistic approach, as there isn’t much room for error or re-working, since the paper’s tooth can hold only a few thin layers of pigment. I rarely use an eraser––I prefer to work with my “mistakes,” enjoying the challenge of resolving them with limited marks. I love the simplicity of the process, and it has taught me a great deal about letting go. I become easily lost in tiny details, and if the pastel and paper did not provide limitations, I fear I would never know when to stop, or when a composition were complete!

Depending on the size and detail of the piece, I spend roughly three to twelve weeks on each drawing. That timeframe continues to increase as I expand the scale and clarity of my compositions.

3. What is one of the most memorable experiences of your professional career as an artist and ocean advocate?

This past winter I completed a five-week art residency in Antarctica, aboard the National Geographic Explorer, led by Lindblad Expeditions. It was my first visit to Antarctica, and I still haven’t found the words to properly convey the majesty and ethereal wonder of this icy continent! In all my travels I have never experienced a landscape as epic and pristine as Antarctica. Ice was the main attraction for me, and it was fascinating to see how in the south, it differed from its northern counterpart.

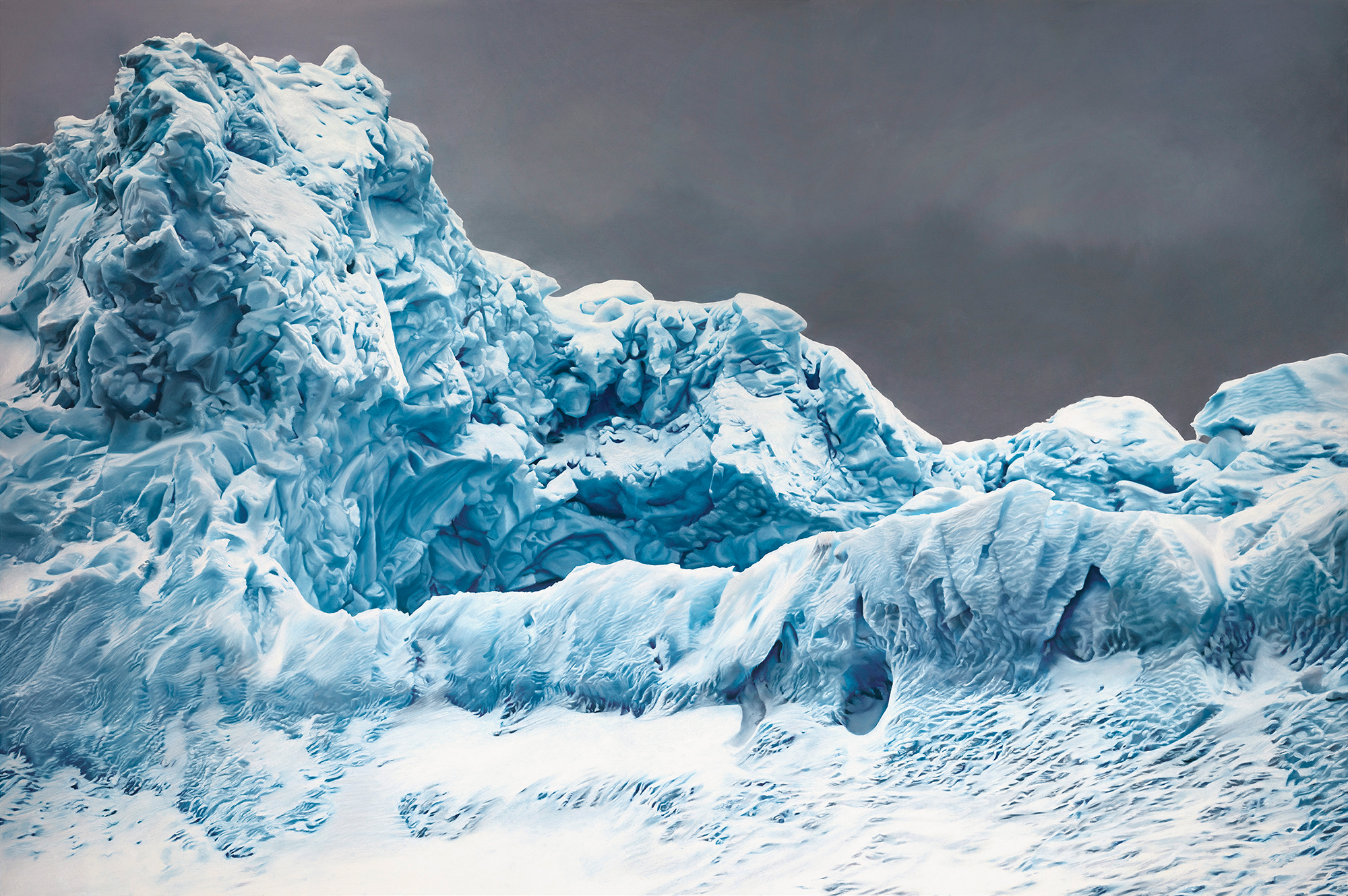

On the Western side of the Antarctic peninsula there is a small place we visited called Whale Bay, which was particularly memorable for me. A glacier near the bay calves icebergs into the sea—as all glaciers eventually do—and the wind and water currents carry these icebergs directly into Whale Bay. Since the bay is somewhat shallow, the icebergs scrape against the sea floor and become “grounded”, meaning they will remain there until they have completely melted – a slow process that can take years if the iceberg is substantial in size. Bays that enclose grounded icebergs like these are called “iceberg graveyards,” a gloomy, yet fitting title that expresses the reverence, silence, and sacredness of this landscape. Throughout the icebergs’ lifespans in the bay, the wind and waves sculpt them into unimaginable shapes. Earth’s elements become artist’s hands to transform graveyards into sculpture gardens.

I had the opportunity to explore Whale Bay for two hours in a small boat, riding around massive, majestic, ice structures. I sat in total awe for every moment. A purple-gray sky loomed above and the winds were calm, creating a tranquility that allowed for perfect reflections of the ice and sky on the water’s surface. Our little boat circled around the most astonishing, intricately sculpted, glowing blue icebergs I have ever seen. I had no idea there were so many shades of bright sapphire blues! I shot hundreds of photographs, and at times had to force my camera into my lap so I could relax and simply experience the breathtaking beauty. I only hope my drawings can capture this awe-inspiring iceberg graveyard, so I can continue sharing this sacred landscape with others.

4. What draws you to the oceans?

I think most human beings are drawn towards any water in one way or another. It makes up more than 75% of our bodies, and it covers most of the Earth’s surface. We need water to survive, but we also gravitate toward its beauty—the respite, shimmer, and movement it adds to a landscape. I think of water as a metaphor for life—forever transforming, both fearsomely and beautifully. It is an endless source of inspiration to me as it constantly changes, taking on new forms from one instant to the next—a movement I attempt to evoke in my drawings. There will always be more for me to learn about the methods with which water can be conveyed in pastel, and I enjoy that never-ending challenge.

5. If you had one message to share, what would it be?

I hope my drawings can facilitate a deeper understanding of the climate crisis, helping us find meaning and optimism in shifting landscapes. One of the many gifts my mother gave me was the ability to focus on the positive, rather than dwell on the negative. I hope my drawings serve as records of landscapes in flux, documenting the transition, and inspiring our global community to take action for the future.

If I had to condense my mission into one message, perhaps it would be “Be kind to the Earth; it sustains us. If we abuse it, we are only causing ourselves great suffering”.

Website: ZariaForman.com

Ted Talk: TEDTalk

Interview: NYPost Video Interview