Jake Price is a creator of visual narratives, using film and photography to record the human experience and chart its connection to our changing earth. After working as a photojournalist and producer at the BBC and New York Times, he shifted his work to filmmaking and immersive media production. Price’s many projects been awarded by the World Press Photo and have also been displayed internationally. Further, he continues to share his experiences by teaching filmmaking and immersive media to the next generation at Columbia University and The International Center of Photography.

-

Lines Aligned, for the Bali International Image Festival, Bali, Indonesia

What was your first introduction to the world of film and video

My first photographic experience occurred in high school when the LA riots broke out. I was sitting in my history classroom looking out the window and could see the smoke rising. I realized at that moment that history was being made and I wanted to document it, not just see it in a book. So I told the teacher I was going to the bathroom and never came back. That happened when I was 16 and I have been photographing and documenting ever since. At the same time, I was also making films on Super 8. I was really interested in European cinema, Ingmar Bergman and François Truffaut being two of the directors who had the greatest influence on me.

-

This was one of the most important photos I have taken. Moments before I was in a shop that was being looted then set on fire. Coming out of it and then later walking down the street I photographed people in the community watching their shops burn. I was taken by the concern and bewilderment on their faces and that became the story for me, not those looting who gained the most sensational coverage.

While your work began as a reaction to the social events that were happening around you, your focus is now on environmental preservation. Are the two connected?

Yes, I always want to have the human narrative as a thread in my work with nature as another character. Ecosystems are like organisms and in their landscape there is as much personality as in a human’s face. There

-

Many nearby homes in Fukushima Province remain abandoned and their fate is not as neat. Unlike the cleaned spaces accessible to the public private property languishes. Unable to move back after the disaster people’s homes are being overrun by weeds and crumbling because of neglect.

What type of environmental disasters have you captured through your work and how have these shifted your perspective on climate change?

The first really big environmental catastrophe that I saw was in Haiti in 2004. There was an American military helicopter flying over the island and one of the marines looking out the window noticed a lake in the place where a town had been the day before. They took the helicopter down and found out that because of the previous night’s rain the whole village had been wiped out. This was because of deforestation—the lack of trees meant that there were no roots to soak up the water. Once word got out about the disaster, I got a call from a French agency I was photographing for at the time and I was on the next flight over. When I arrived, I got word that I was on assignment for

The New York Times

. That was my first real eye-opening experience to the reality of environmental disasters.

The following year, Hurricane Katrina happened and since then it just has picked up immensely. There hasn’t been a time since then that I haven’t seen a huge environmental disaster every year. As far as I am concerned, that is inarguably the result of climate change. For children born after 2004, this has been their reality—they only know extreme events as normal weather. My niece has never known the typical four seasons, as I grew up knowing. It’s frightening to think that there has been so much change between

my generation and hers

and what will be coming next.

-

A group of earthquake survivors in 2010 who were relocated from the Petionville camp in Port au Prince arrive in the Corail-Cesselesse camp which was promised to be safer and better equipped than the Petionville camp.

Much of your prior experience in photography revolves around journalism, but your recent photographic series on the Gowanus Canal has shifted towards the realm of fine art. How does the tone of your journalistic work differ from your art practices?

Although both of my practices are highly connected, I feel more at home addressing my concerns in cinematic and artistic ways. Right now, I think that journalism is having a hard time addressing climate change because it’s stuck primarily documenting the dramatic moments and the aftermaths with imagery that we’ve seen a million times. All of the flooded streets and wasted landscapes I documented starting blending together and became repetitive. Although it was important to document these incidents, I felt that a new visual language was needed. I think that a cinematic approach lets people look at things in more dimensional ways. The fact of the matter is that so much poison is flowing down the Gowanus Canal, but art lets us look at this issue more abstractly, which invites questions and a different engagement.

-

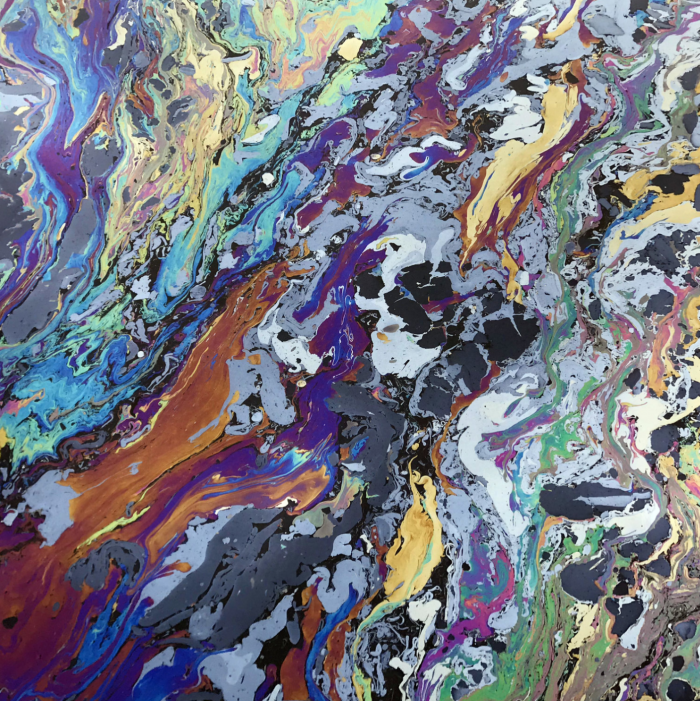

This is a photo of pollution running down the Gowanus canal which has not been altered. This is what it looks like on days when the pollution is at its worst, which is typically at low tide or after it rains. The pollution empties out into the Upper Bay and ultimately into the Atlantic Ocean.

Some of your biggest projects have centered around Fukushima and the nuclear disaster which occurred there following the 2011 earthquake. How did you begin exploring the history of this place and how does this story contribute to the larger story of humans and our connection to landscape?

My work with Fukushima continues to manifest itself in different forms; from immersive online projects, such as Unknown Spring and The Invisible Season , to installation pieces —and now a film.

-

Recovered photos that were found in the wreckage of the tsunami, 2011.

Fukushima was a paradise before the explosions poisoned the land with radiation. But the world knew nothing of Fukushima before the meltdown and now only knows it as a wasteland. Much of it is still a wasteland, but it’s also tremendously beautiful. Some of the best rice, vegetables, fish, and meat in Japan came from Fukushima. As I heard the stories of the people who used to live there, I realized that I had to tell not only the stories of disaster but also tales of love. So in my interview series for Fukushima, I focused on speaking with people about all that they deeply cared for in the region. In doing so, I wanted the audience to think of Fukushima as their backyard. I wanted them to see that the landscapes that they hold dearly in their lives—whether that’s the beautiful farmland in Provence or the Hudson Valley in New York—are just as fragile as what was lost in Fukushima.

In that way, Fukushima becomes not just a place in Japan but a place that is connected to all of our lives. I think there is an added incentive to preserve things, especially if we understand the value of that which is around us.

-

Spaces for daily life have been overtaken by nature, after the people of Fukushima were forced to leave.

For now, the debate on climate change has often been presented as one of belief versus disbelief. Do you think by considering climate change through the lens of culture we can turn it into a bi-partisan issue?

I really hope so. Although art is usually more left-leaning I think it has the power to unite us in our common culture. One especially important facet of this is the food we eat: it can literally bring us to the table and show us our shared humanity. It speaks to those of us who have a strong sense of national identity and also to those who are concerned with the land and the bodies we live in. My upcoming project, An Uncertain Land , explores the link between land, food and culture and all that we stand to lose if we do not urgently address climate change. By focusing on food and the loss of culinary heritage, climate change becomes a lot less abstract. Can you imagine a world without buffalo mozzarella, a Georgia peach or a gorgeous bottle of Bordeaux? It’s not hard to imagine that all we love to eat can disappear if we don’t get things under control.

-

Remnants of a meal, left behind in Fukushima.

To learn more about the work of Jake Price, check out the links below.

Websites: JakePrice.com; TheInvisibleSeason.com; UnknownSpring.com

Instagram: @jakepricenyc

Author: Carola Dixon

Editor: Dena Silver

Instagram: @jakepricenyc

Author: Carola Dixon

Editor: Dena Silver